The Dawn of the Image: Unveiling the Birth of Photography

Introduction

Photography, in its myriad forms, is an omnipresent force in contemporary life. From the casual snapshots captured on smartphones to the intricate imagery produced by advanced scientific instruments, it fundamentally shapes how individuals perceive, remember, and interact with the world. This pervasive role often belies the profound marvel of its origins and the centuries of human ingenuity and relentless scientific pursuit that led to its invention.

For millennia, humanity harbored a deep-seated desire to capture fleeting visual reality beyond the ephemeral stroke of a painter’s brush or the fleeting glance of the eye. This persistent quest fueled centuries of experimentation in optics and chemistry, laying the intellectual and technical groundwork for photography’s eventual emergence. The birth of photography was not a singular, isolated invention but rather a complex, iterative process. It was driven by groundbreaking scientific discoveries that unlocked the secrets of light and chemistry, coupled with the persistent artistic and societal need to permanently record the world. This revolutionary new medium would profoundly reshape artistic expression, advance scientific understanding across diverse disciplines, and democratize visual representation, forever changing how humanity perceives and interacts with reality.

Centuries in the Making: The Precursors to Photography

The journey toward photography began long before the 19th century, rooted in two distinct but ultimately converging scientific principles: the optical projection of images and the chemical alteration of substances by light.

The Camera Obscura: From Ancient Observations to Artistic Aid

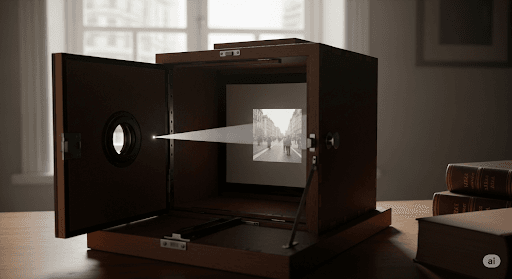

The conceptual foundation for photography, the camera obscura (Latin for “dark chamber”), dates back to antiquity. Its fundamental principle, where light passes through a small aperture into a darkened space to project an inverted image of the external world, was recognized by various cultures, including Aristotle and the Chinese, over 2000 years ago. Records indicate its use as early as 500 B.C. or the 4th century BCE. This widespread and ancient knowledge of the camera obscura highlights that the optical principle of photography was understood for millennia. The initial challenge, therefore, was not merely image projection, but the ability to make these fleeting images permanent.

For centuries, the camera obscura served primarily as an artistic tool. Painters and draftsmen utilized it to trace the projected images, aiding in the creation of accurate perspectives and realistic depictions. This method remained a popular aid for recording images until the early 1800s. The limitation was clear: while the camera obscura could render reality with remarkable fidelity, it offered no means to chemically fix or preserve these ephemeral visuals. This distinction is crucial for understanding the true nature of the 19th-century breakthroughs; the core problem to be solved was the chemical permanence of the image.

The Spark of Photochemistry: Early Discoveries of Light-Sensitive Materials

Parallel to the optical understanding of the camera obscura, scientific inquiry into light-sensitive materials began to develop significantly in the 18th century. Johann Heinrich Schulze, in 1727, made a pivotal discovery: he demonstrated that certain silver salts darkened when exposed to light, not heat, by using sunlight to “write” words with them. This laid the chemical groundwork for what would become photochemistry.

Building on this nascent understanding, English physicist Thomas Wedgwood and chemist Humphry Davy experimented around 1800 with silver nitrate and chloride. They successfully produced images, particularly silhouettes and other shadow images through contact printing on treated leather or paper. However, a critical limitation persisted: they were unable to make these images permanent; they would inevitably fade away when subsequently exposed to light for viewing. Their attempts to capture images with a camera obscura also proved unsuccessful, as the projected images were too faint to adequately affect the silver nitrate. The inability of Wedgwood and Davy to achieve permanence underscores the immense technical hurdles that remained. The “age of photography” truly began when these two distinct scientific paths—optical projection and chemical fixation—converged. This convergence, rather than a singular discovery, represents the deeper theme that defines photography’s birth.

The Pioneering Triumvirate: Defining the First Images

The early 19th century witnessed the groundbreaking work of three key figures whose independent and collaborative efforts laid the definitive foundation for photography as a practical medium: Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, Louis Daguerre, and William Henry Fox Talbot. Their innovations, though distinct, collectively propelled photography from a scientific curiosity to a revolutionary technology.

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce and Heliography

The French inventor Joseph Nicéphore Niépce is widely recognized as the pioneer of photography and the creator of the first permanent photographic image. While his earliest works from 1822 have unfortunately been lost to history , his “View from the Window at Le Gras,” captured in 1826 or 1827, stands as the oldest surviving camera photograph. This monumental achievement marked the true beginning of the age of photography.

Niépce’s innovative process, which he termed “heliography” (meaning “sun drawing”), involved coating a polished pewter plate with a light-sensitive substance known as Bitumen of Judea (a natural asphalt). He would prepare this by dissolving powdered bitumen in lavender oil, applying a very thin layer to the plate, and then drying it to create a shiny, cherry-red varnish. The coated plate was then inserted into a camera obscura and exposed to sunlight for an extraordinarily long duration—ranging from eight hours to several days in broad daylight. After this prolonged exposure, the parts of the bitumen that had not been hardened by light were dissolved away using solvents like lavender oil, leaving a permanent positive image. Niépce’s contribution went beyond simply producing the first photo; his experiments revealed photography’s potential for both original creation (capturing real-life scenes with a camera obscura) and mechanical reproduction (copying existing engravings). The extremely long exposure times were a significant technical limitation, explaining why his subjects were static, such as a view from a window, and highlighting the immense technical hurdles that would drive subsequent innovations and the crucial need for faster processes.

Louis Daguerre and the Daguerreotype

Recognizing the immense potential of Niépce’s work, Louis Daguerre, a renowned French painter and diorama proprietor, partnered with Niépce in 1829 to further improve the photographic process. Following Niépce’s death, Daguerre continued their collaborative work, culminating in his invention of the daguerreotype in 1837. This groundbreaking process was publicly announced in Paris in 1839, marking a significant moment in photography’s history. The public announcement was crucial, as it democratized access to the knowledge of photography, even if the process itself remained complex and costly.

The daguerreotype involved meticulously polishing a sheet of silver-plated copper to a mirror finish. This plate was then treated with fumes from iodine, and later bromine or chlorine, to make its surface highly light-sensitive. After exposure in a camera, the latent image was developed using mercury vapor, which reacted with the silver halides to form the visible image. Finally, the image was fixed permanently using a salt solution, specifically sodium thiosulfate (known as “hypo”), a discovery improved by Sir John Herschel.

This innovation dramatically reduced exposure times from hours to minutes, initially requiring up to 30 minutes but later reduced to a mere fifteen to thirty seconds in favorable lighting conditions. The daguerreotype produced images with unprecedented detail and sharpness, capable of recording fine detail at a resolution that even 2000s digital cameras struggled to match. Daguerre’s “Boulevard du Temple” (1838) is particularly notable as the first photograph believed to show a living person, albeit blurred due to the long exposure. This significant step forward in image quality and exposure speed directly addressed the limitations of Niépce’s heliography, making portraiture—a major social demand—viable.

Despite its remarkable quality, the daguerreotype produced a singular, unique image on each plate; no direct copies could be made from the original. The highly polished silver surface was extremely delicate and prone to permanent scuffing and tarnishing, necessitating protective cases. Early lenses were “slow” (around f/14), making portraiture challenging as subjects still had to remain perfectly still for minutes. This “one-of-a-kind” nature was a critical limitation that directly contrasted with Talbot’s simultaneous breakthrough, setting up a clear dynamic in the early photographic landscape.

William Henry Fox Talbot and the Calotype

Concurrently with Daguerre’s work, the English polymath William Henry Fox Talbot was independently experimenting with light-sensitive materials. He successfully developed a method for recording images as early as 1835, and by 1839, he had found a way to make these images more permanent. His process was later named the “calotype” (from the Greek and Latin words for “beautiful image”) by his friend, the noted astronomer Sir John Herschel, who also famously coined the term “photography” (“writing with light”) and suggested using sodium thiosulfate (known as “hypo”) for improved fixing, a method immediately adopted by both Talbot and Daguerre.

Talbot’s method involved treating high-quality writing paper with a salt solution and then silver nitrate to create a light-sensitive silver chloride surface. This specially prepared paper was then exposed in a camera to create a negative image. From this single negative, multiple positive prints could then be made. The calotype’s most profound advantage over the daguerreotype was its inherent ability to produce multiple positive prints from a single negative. This reproducibility was a game-changer, making photography more accessible, portable, and cost-effective for wider distribution. It also allowed for easier retouching and manipulation of the negative, offering photographers more creative control. This negative-positive process was a foundational conceptual breakthrough, establishing the principle that would underpin most of photography for the next 150 years. While initially less sharp than daguerreotypes , its reproducibility was a critical enabler for mass distribution and the eventual commercialization of photography, illustrating a crucial tension in early photographic development: the trade-off between ultimate image quality and practical utility for mass production.

Despite its versatility, calotypes generally produced softer, more “sketchy” images compared to the daguerreotype’s crystalline detail, largely due to the fibrous texture of the paper negative showing through in the prints. Early calotypes were also prone to fading and deterioration over time, requiring careful storage and limiting their long-term viability. Due to these factors, the initial picture quality made it less popular than the daguerreotype in its early years, especially in the United States.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Early Photographic Processes

| Feature | Heliography (Niépce) | Daguerreotype (Daguerre) | Calotype (Talbot) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inventor(s) | Joseph Nicéphore Niépce | Louis Daguerre (with Niépce’s prior collaboration) | William Henry Fox Talbot |

| Approximate Date | 1826/1827 (first permanent) | 1837 (invented), 1839 (publicly announced) | 1835 (invented), 1839 (made permanent) |

| Process Name | Heliography | Daguerreotype | Calotype (also “Talbotype”) |

| Base Material | Pewter plate | Silver-plated copper sheet | Paper |

| Key Chemical Agent(s) | Bitumen of Judea | Iodized silver (developed with mercury fumes) | Silver chloride (from salt and silver nitrate) |

| Initial Exposure Time | 8 hours to several days | Minutes (initially 30, later 15-30 seconds) | Minutes to hours (later reduced to 1 minute) |

| Reproducibility | No (direct positive) | No (unique direct positive, copies via re-daguerreotyping) | Yes (multiple prints from a single negative) |

| Image Quality | Faint, low detail | Extremely sharp, high detail, mirror-like | Softer, “sketchy” due to paper fibers |

| Durability/Fragility | Permanent but required illumination for viewing | Very delicate, prone to scuffing and tarnishing | Prone to fading and deterioration over time |

| Key Advantage(s) | First permanent image | Unprecedented sharpness, reduced exposure time | Reproducibility, portability, cost-effectiveness |

| Key Limitation(s) | Extremely long exposure, low detail | Unique image (no direct copies), fragile surface, costly | Softer image, stability issues over time |

The Rapid Evolution: From Lab to Public Domain (1840s-1860s)

The foundational discoveries of Niépce, Daguerre, and Talbot ignited a period of intense innovation, rapidly transforming photography from a complex laboratory endeavor into a more accessible and commercially viable medium. The decades following 1840 witnessed a proliferation of new techniques and applications that brought photography closer to the public.

The Wet Collodion Process (Frederick Scott Archer)

The 1850s marked a significant period of transition and rapid advancement in photography, as new processes began to be adopted more broadly. Frederick Scott Archer, an English sculptor and photographer, invented the wet collodion process in 1851, seeking a method that produced sharper prints and required shorter exposure times than existing methods. This technique involved coating a clean glass plate with collodion (a solution of guncotton dissolved in ether), which was then made photosensitive by immersion in a bath of silver nitrate.

The wet collodion process was a major leap forward, offering significantly sharper and more detailed images than calotypes due to the smooth, grainless glass negative. It also drastically reduced exposure times to just a few seconds , making it approximately 20 times faster than previous methods. Crucially, like the calotype, it produced a negative from which numerous positive prints could be made, effectively combining the best aspects of both Daguerreotypes (sharpness) and Calotypes (reproducibility). Furthermore, the method was generally cheaper than other available processes. This process represents a critical synthesis in photographic history, effectively combining the high resolution of daguerreotypes with the reproducibility of calotypes, marking a pivotal shift from the experimental phase to a more commercially viable and widely adopted medium.

The primary drawback of the wet collodion process was that the glass plate had to be exposed and developed while the collodion coating was still wet. This necessitated photographers to travel with portable darkrooms and heavy equipment, including multiple chemicals, making on-site development a logistical challenge. Despite this practical difficulty, its superior quality, speed, and reproducibility led it to dominate photography for the next three decades. Archer notably did not patent his process, believing in sharing the medium without restriction, which further encouraged its rapid spread and production. This decision demonstrates how intellectual property choices can significantly impact technological diffusion and adoption. The logistical challenges also highlight the ingenuity and dedication of early photographers who adapted to these demanding requirements.

Albumen Prints: The Era’s Dominant Printing Medium

Invented by Louis Désiré Blanquart-Evrard in 1850, albumen prints rapidly became the preferred medium for producing positive prints from the sharp wet collodion negatives. These prints were created by coating paper with a layer of egg white (albumen) and salt, which provided a smooth, glossy surface. This coated paper was then sensitized with silver nitrate, forming light-sensitive silver salts. When placed in contact with a negative and exposed to light, it produced highly detailed photographs in rich, brown tones.

Albumen prints remained the most common type of photographic print for approximately 40 years, dominating the market until the late 19th century. The widespread adoption of albumen prints signifies the standardization of the output aspect of photography. This consistency in print quality and appearance was crucial for the growing commercial demand for photographs, allowing for mass production and distribution. This development illustrates how the ecosystem of photography was maturing beyond just capturing an image to effectively disseminating it to a broader public.

Democratizing the Image

The mid-19th century saw photography transition from a specialized craft to a truly mass medium, profoundly impacting social interaction and personal identity.

The Carte-de-Visite

A major driver of photography’s popularization was the carte-de-visite, introduced by André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri in Paris in 1854. These were small, relatively inexpensive photographic portraits, typically measuring about 2.5 x 4 inches, the size of a traditional calling card. Disdéri ingeniously used a multi-lens camera to produce eight negatives on a single glass plate, significantly reducing production costs and enabling mass production.

The carte-de-visite became immensely popular in the 1860s, quickly transforming into “social currency”. People avidly collected these “card-portraits” in albums and exchanged them among friends, family, and distant acquaintances. This allowed for a new form of “virtual self-presentation” and social performance, anticipating aspects of modern social media. Its ubiquity was astounding; in England alone, 300 to 400 million cartes were sold annually between 1861 and 1867. The affordability and reproducibility of these formats directly led to the “democratization of the image,” making photography a part of everyday life and social interaction for a broader public, not just the elite. The “social currency” aspect of cartes-de-visite demonstrates how photography immediately influenced social norms and personal identity.

Stereoscopy

Another phenomenon that captivated audiences was stereoscopic photography. Stereoscopic views (stereographs) became a worldwide craze from the mid-1850s through the early years of the 20th century. First described by English physicist Sir Charles Wheatstone in 1832 and improved by Sir David Brewster in 1849, stereographs involved taking two images of the same subject with a dual-lens camera, mimicking human binocular vision. When viewed through a stereoscope, these side-by-side images merged to create a powerful illusion of three-dimensionality.

Stereoscopy served as both an educational and recreational device, bringing distant landscapes, monuments, and composed narrative scenes into homes, much like television or virtual reality today. Its immense popularity, particularly after Queen Victoria expressed interest in it at the 1851 Crystal Palace Exposition, meant that stereographs were the first encounter with photography for many people. The “3D craze” of stereoscopy highlights the public’s fascination with the new medium’s capabilities beyond simple flat images.

Table 2: Key Innovations and Their Impact on Photography’s Accessibility

| Innovation/Process | Approximate Date | Key Technical Feature | Impact on Accessibility/Cost/Usage | Resulting Social/Commercial Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wet Collodion Process | 1851 | Glass negatives, high sharpness, short exposure times | Enabled multiple prints, combined quality and reproducibility | Professional portraiture, war reportage |

| Albumen Prints | 1850 | Egg white coating for smooth, glossy surface | Standardized print quality, facilitated mass production | Widespread commercial prints, albums |

| Carte-de-Visite | 1854 | Multi-lens camera for 8 negatives on one plate, small size | Reduced cost for portraits, enabled mass distribution | Personal portraits, social exchange, celebrity cards |

| Stereoscopy | Mid-1850s | Dual-lens camera for two images, viewed through stereoscope | Created 3D illusion, brought distant scenes to homes, educational | Home entertainment, travel documentation, educational tool |

| Dry Plate Technology | 1871 | Pre-coated glass plates, no immediate development needed | Freed photographers from portable darkrooms, increased flexibility | Outdoor photography, travel, amateur use |

| Flexible Roll Film | 1880s | Flexible film on rolls | Lighter, more resilient, allowed multiple quick shots | Mass-market cameras (Kodak Brownie), amateur photography |

A World Transformed: Photography’s Early Impact

The advent of photography was not merely a technical achievement; it profoundly reshaped artistic expression, advanced scientific understanding, and irrevocably altered societal interactions and self-perception.

Reshaping Art

Photography’s unprecedented ability to depict reality with precise accuracy immediately challenged painting’s centuries-old role as the primary visual record-keeper. This “realism paradox” profoundly impacted the art world, forcing painting to “reinvent itself.” Artists began to shift their focus from mere objective representation to portraying emotions, impressions, and internal realities, thereby paving the way for revolutionary art movements like Impressionism and Expressionism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Photography’s capacity for realism paradoxically freed painting from this constraint, pushing it towards abstraction and subjectivity.

While initially dismissed by some as a purely mechanical process incapable of true art , pioneering photographers soon demonstrated its profound artistic potential. Movements such as Pictorialism, emerging around 1885, actively manipulated images through careful posing of subjects, sophisticated darkroom techniques, and even overpainting to achieve aesthetic effects reminiscent of traditional painting, thereby asserting photography’s creative merit. This artistic ambition led to the formation of dedicated photographic societies, periodicals, and juried exhibitions, solidifying photography’s place as a legitimate art form. This dynamic interaction, where one art form’s strength influenced another’s evolution, is a profound implication of photography’s birth, demonstrating that it too involved creative control and expression.

Advancing Science

From its very inception, photography proved to be an indispensable scientific tool. Its objective nature and ability to capture details invisible to the naked eye and phenomena too quick for human perception revolutionized observation and documentation across various scientific fields. Photography became the “eye” of modern science.

In astronomy, the first photograph of an astronomical object was a blurred image of the Moon by Daguerre in 1839, followed by John William Draper’s first successful image in 1840. The first star (Vega) was photographed in 1850 by William Cranch Bond and John Adams Whipple. A major breakthrough came in 1880 when Henry Draper captured the first photograph of a deep-sky object, the Orion Nebula, revealing stars too faint for the human eye. Photography became crucial for star cartography, astrometry, and spectroscopy, fundamentally changing how celestial bodies were studied.

In medicine, photography dates back to the mid-1840s with Alfred François Donné’s photomicrograph atlas of medical specimens and early patient portraits in 1847. Clinicians like Hermann Wolff Berend and Hugh Welch Diamond began consistently using photography in the early 1850s to diagnose diseases, monitor treatment progress, and evaluate physiognomy. Photographic atlases of dermatological diseases emerged (e.g., Alexander John Balmanno Squire, 1865), and neurologists like J.M. Charcot used photography extensively for clinical observation, research, and teaching, incorporating it into the everyday activity of hospitals.

For geology and environmental science, photographers such as William Henry Jackson and Carleton Watkins documented the American West as part of government-sponsored geological surveys in the 1860s and 1870s, providing invaluable scientific data on land use, soil erosion, and ecosystems. Aerial photography, initially conducted from balloons in the 19th century, also emerged as a powerful remote sensing tool for surveying and mapping.

The very development of photography relied on continuous advancements in optics and chemistry. Conversely, the medium became an essential tool for scientific investigation, pushing the boundaries of what could be observed, documented, and understood across countless disciplines. This illustrates a powerful feedback loop where scientific needs drove photographic innovation, and photographic capabilities advanced scientific understanding.

Mirroring Society

Photography’s societal impact extended far beyond mere documentation; it profoundly reshaped social structures and individual identity. Before photography, a painted portrait was a luxury reserved for the wealthy elite. The advent of the daguerreotype made portraiture more accessible, and subsequent processes like the calotype and especially the mass-produced carte-de-visite made personal likenesses inexpensive and widespread, allowing middle and even lower classes to possess their own images. This empowered individuals to consciously construct and transmit their self-image, acting as a powerful means of social ascent and self-expression. Notably, abolitionist Frederick Douglass famously advocated for photography as a means for African Americans to counter negative stereotypes with positive, dignified self-images. This shift from an elite luxury to mass accessibility highlights photography’s role as a social equalizer and identity builder.

Photography profoundly transformed how social events were captured and remembered. It provided a new, objective way to immortalize important family events such as weddings, first communions, and even post-mortem commemorations. Photographs quickly became a crucial element of the illustrated press, making images of public figures and distant places accessible to a wider audience, functioning as an early antecedent to modern news media. The ubiquity of images fostered new social norms around sharing, collecting (e.g., carte albums), and self-expression, fundamentally changing social interaction and the construction of collective memory. The “social currency” aspect of cartes-de-visite demonstrates its deep cultural integration, showing how photography became an active agent in shaping public perception, facilitating social mobility, and creating new forms of collective memory and communication, laying groundwork for today’s visual culture.

Conclusion

The dawn of photography was not a singular moment but a testament to relentless human curiosity and innovation. From the ancient optical principles of the camera obscura to the early photochemical experiments, the stage was set for a revolution. Joseph Nicéphore Niépce’s pioneering heliography paved the way, followed by Louis Daguerre’s exquisitely detailed daguerreotypes and William Henry Fox Talbot’s revolutionary negative-positive calotypes. Subsequent developments like Frederick Scott Archer’s wet collodion process, the widespread use of albumen prints, and the popularization of formats like cartes-de-visite and stereoscopy rapidly refined the medium, making it sharper, faster, and increasingly accessible.

Photography’s birth irrevocably altered the landscape of art, pushing traditional painting towards new expressions while firmly establishing itself as a powerful and legitimate artistic medium. It became an indispensable tool for scientific discovery and objective documentation across myriad fields, from charting distant stars to diagnosing human ailments and mapping geological formations. Most profoundly, photography democratized the image, empowering individuals to represent themselves, transforming societal communication, and shaping collective memory in ways that continue to resonate deeply in our increasingly visual digital age. The extraordinary journey from light-sensitive bitumen to instant digital sharing is an enduring testament to humanity’s ongoing quest to capture, comprehend, and share the world around us.